The Activist Investor Blog

What’s a Universal Proxy, and Why Does Nelson Peltz Care?

We thought only corp gov junkies care about this subject, we certainly didn’t. Now that Nelson Peltz cares, we think we’ll start.

In his current efforts at DuPont, Peltz proposed the company use a “universal proxy card” (UPC) for the upcoming proxy contest. The company declined, setting off another round of acrimony.

Much as Carl Icahn promotes a range of targeted corp gov changes to pressure recalcitrant portfolio companies, Peltz skillfully did something similar. As he makes the case for his nominees, he can claim that DuPont disenfranchised shareholders by rejecting a favorite corp gov reform.

Sort of Like Proxy Access, But Not Quite

Simply put, a UPC lists all nominees for a BoD on a single proxy card or ballot. The company lists both the incumbent directors, and a shareholder’s nominees. A shareholder also lists its nominees, and the company’s.

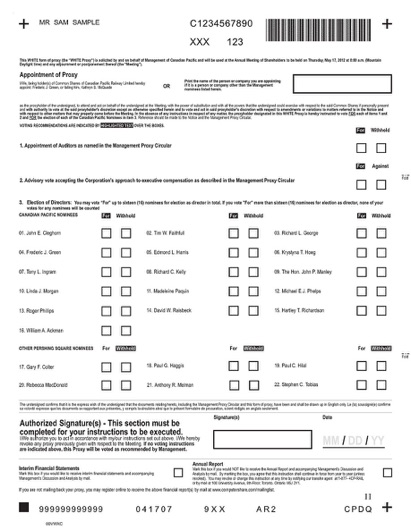

We could find only one recent example of a UPC:

Bill Ackman at Pershing Square persuaded Canadian Pacific to use this proxy card for the proxy contest in 2012.

The company and the shareholder each send a UPC to all shareholders. Shareholders thus vote for the nominees that they want to support, from among both the company and shareholder candidates. A shareholder need not vote for only the company or shareholder nominees, as they do under the usual system.

Both the company and the shareholder still need to file and send proxy materials to all shareholders. In those materials, the company need not include information about shareholder nominees in the company proxy materials, and vice versa.

In contrast, with proxy access, the company sends out all the proxy materials, and the shareholder need not. A UPC consolidates only the act of voting, not investor communication.

Why Use a UPC? Why Not?

The UPC allows a shareholder to split votes between company and shareholder nominees (proxy access does this, too). This interests investors that seek to elect one or a few BoD nominees without gaining control. This in turn appeals to shareholders that support change at a company, but don’t want to turn out the entire BoD.

It gets really cumbersome, though. An arcane regulatory technicality (“bona fide nominee” rule) prevents US companies from using it, or at least allows companies like DuPont to claim it makes the election more complicated, not less.

One company tried a form of UPC a couple of years ago. Starboard sought to elect directors at Tessera in 2013. Tessera proposed a proxy card in which it nominated six out of eight incumbent directors, and allowed shareholders to write-in (like, with a pencil) the names of two Starboard nominees. The SEC did not allow this, though, based on that technicality.

Institutional investors love, love, love the UPC. The CII has made it a priority for years.

The SEC considers UPCs periodically, and whether to clear up the regulatory issue. Last month, a roundtable debated the subject for a day, with shareholders in favor, and companies opposing, similar to the current positions on proxy access.

Pressure at DuPont

Peltz probably doesn’t (or shouldn’t) care too deeply about the UPC. He nominated four directors for a twelve-person BoD, and it doesn’t much matter which incumbents his nominees replace. It also doesn’t matter to other shareholders, most of which either support his four, or don’t. Splitting votes becomes less relevant.

This bit of corp gov business, though, appeals to many of the institutions that own DuPont shares. At least a few of those investors will think less of DuPont and its BoD now. In a close contest like this, with competing business cases, Peltz makes the DuPont BoD look more interested in its own entrenchment, and less in the success of the company. Targeted corp gov changes, once again.

Well played.

Tuesday, March 10, 2015